Distinguishing Federal Business Development From Capture

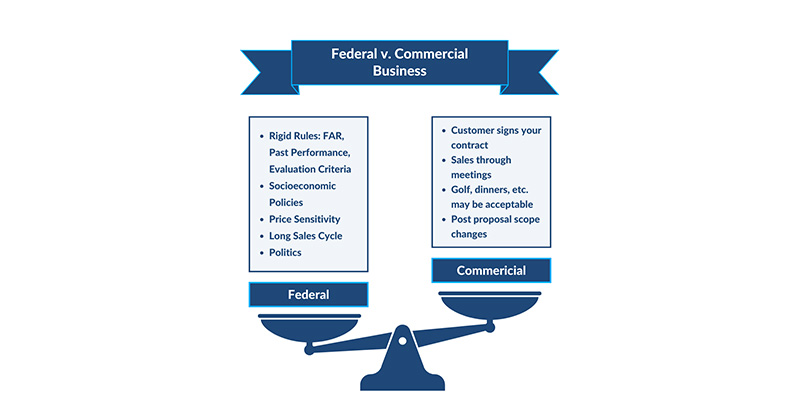

In the realm of federal contracting, the terms “business development” and “capture” are frequently used interchangeably, leading to confusion and misinterpretation. These two functions play distinct yet complementary roles in the pursuit of government contracts. Understanding the nuances between business development and capture is helpful for organizations aiming to navigate the complex landscape of federal procurement successfully.

Business Development: Pioneering Growth Opportunities

At its core, business development encompasses the strategic process of identifying and cultivating relationships with potential customers, partners, and stakeholders. In the federal context, business development focuses on exploring and creating opportunities within the government sector to expand an organization’s brand awareness, market presence, and revenue streams.

Business development professionals engage in market research, analysis, and relationship-building activities to uncover pain points, emerging needs, trends, and opportunities within government agencies. They leverage networking events, industry conferences, and outreach initiatives to establish connections and position their organization as a trusted partner capable of delivering value-added solutions.

The objective of business development is to lay the groundwork for future success by participating in the larger GovCon community, identifying potential leads, understanding customer requirements, and shaping acquisition strategies. It involves a proactive, long-term approach aimed at fostering strategic partnerships and positioning for competitive advantage in the federal marketplace.

Capture for Contract Wins

Capture management, on the other hand, is a focused and tactical approach aimed at pursuing specific government contracts identified through the business development process. While business development sets the stage, capture management is the orchestration of activities to win a particular contract.

Capture professionals work closely with internal resources, such as the BD team, technical experts, proposal writers, finance and pricing, legal, and executive leadership, to develop comprehensive capture plans specific to each opportunity. A capture plan outlines the organization’s strategy for positioning, differentiation, pricing, and proposal development, with an eye on maximizing win probability.

Key components of capture management include competitive analysis, customer engagement, solution development, teaming strategies, and proposal preparation. It requires a deep understanding of customer requirements, acquisition regulations, and competitive landscapes to craft compelling value propositions that resonate with government decision-makers. Unlike business development, capture management has a singular goal of securing a contract win.

Why It Matters

Understanding the difference between federal business development and capture is important for managing the growth function within a company and effectively pursuing and winning government contracts. Here’s why:

- Ensuring Focus: Organizations that do not have a strong capture process often fall victim to attempting to “boil the ocean,” which results in expending excessive resources, time, and effort pursuing opportunities that may not align with the organization’s capabilities or strategic objectives. To avoid stretching business development to thin, it’s necessary to focus efforts. A common way to drive focus is implementing a structured capture process.

- Resource Allocation: Whereas business development is broad and involves activities such as opportunity identification and federal marketing, capture is opportunity specific and the activities are more resource-intensive, involving detailed proposal development, teaming arrangements, and solution design. By distinguishing between the two, organizations can appropriately articulate their objectives for BD and capture and better allocate the right resources maximize their chances of success.

- Risk Management: Effective capture management involves identifying and mitigating risks associated with pursuing a particular opportunity. This includes assessing factors such as competition, customer requirements, and budget constraints. The capture process builds in the ability for organizations to make informed decisions about which opportunities to pursue.

- Customer Relationship Management: Business development activities often involve building and maintaining relationships with federal agencies, prime contractors, and other stakeholders. Capture management involves engagement with specific customers and partners to position for specific contracts. By understanding the distinction between the two, organizations can tailor their approach to relationship management accordingly.

- Inadequate Solution Development: Without a systematic approach to solution development within the capture process, organizations may struggle to tailor their offerings to meet the specific needs and requirements of federal agencies. This can result in generic or poorly aligned proposals that fail to resonate with agency decision-makers.

- Proposal Development: Capture management culminates in the development of a detailed proposal in response to a specific opportunity. A dedicated capture process ensures that an organization’s proposal development efforts are aligned with the needs of the customer and the competitive landscape.

- Reputational Damage: Submitting subpar proposals, failing to deliver on commitments, or exhibiting unprofessional behavior during the procurement process can result in reputational harm. This can negatively impact future opportunities and relationships within the federal market. Proper proposal development, teaming agreements, and rigorous processes included in capture management help ensure rules of engagement and pursuit are developed and followed.

Harmonizing Business Development and Capture

While distinct, business development and capture are inherently connected and mutually reinforcing. Effective business development lays the groundwork by identifying potential opportunities and cultivating relationships, while capture management capitalizes on these connections and insights to pursue and win specific contracts.

Successful organizations recognize the relationship between business development and capture, integrating both functions seamlessly within their overall growth strategy. They invest in robust processes, technology, and talent to align business development efforts with capture objectives, ensuring a cohesive and coordinated approach to federal contracting.

While the terms “business development” and “capture” may often be used interchangeably, their roles and functions within the federal market are distinct but complementary. By understanding the nuances between business development and capture and harmonizing both functions effectively, organizations can maximize their competitiveness, drive sustainable growth, and capitalize on the vast opportunities offered by the federal marketplace.

About the author:

MJ Sivulich is a Senior Vice President and leads Jefferson’s business solutions practice. MJ provides federal business development, capture, proposal, government affairs, and marketing support to industry clients. To contact the author or learn more about Jefferson’s federal business development services, please email contact@jeffersonsg.com.